Being an illustrator has to be one of the most fulfilling creative professions. After all, you get to create pieces of art day in, day out, and someone will pay you to do so while you’re still living. But what does an illustrator do when they reach the top of their game and remain there for a decade or more, while gradually losing interest in being an applied artist? For Toronto-based artist Derek Lea, the answer was to press the reset button and start again as a painter.

Being an illustrator has to be one of the most fulfilling creative professions. After all, you get to create pieces of art day in, day out, and someone will pay you to do so while you’re still living. But what does an illustrator do when they reach the top of their game and remain there for a decade or more, while gradually losing interest in being an applied artist? For Toronto-based artist Derek Lea, the answer was to press the reset button and start again as a painter.

“Illustration is applied art, it is always commissioned and you are ultimately solving problems for clients at the end of it. The great part of it is that a lot of people will see your work. The content is born of necessity to the problem at hand. That being said, I was very fortunate to have clients that wanted me to explore,” says Derek, who became known around the world as a leading Photoshop artist.

He continues: “Working digitally was all about curiosity in the beginning and that was what drove me and made me enthusiastic. After a while, that all went away and it became a job. I was taking on jobs just to make money and sometimes I was mailing it in with minimal effort. I felt like my creativity could have a higher purpose than that so I quit doing it.”

Was he crazy?

Was he crazy?

When he finally gave up illustrating several years back, he knew it was a crazy move. He had clients like the Toronto Star newspaper, and magazines like Computer Arts in the UK, and Discover in New York. He’d written two books about digital illustration – Creative Photoshop and Beyond Photoshop – with several updated editions of each. And some of his clients were surprised when he downed tools. They just don’t get that from many illustrators.

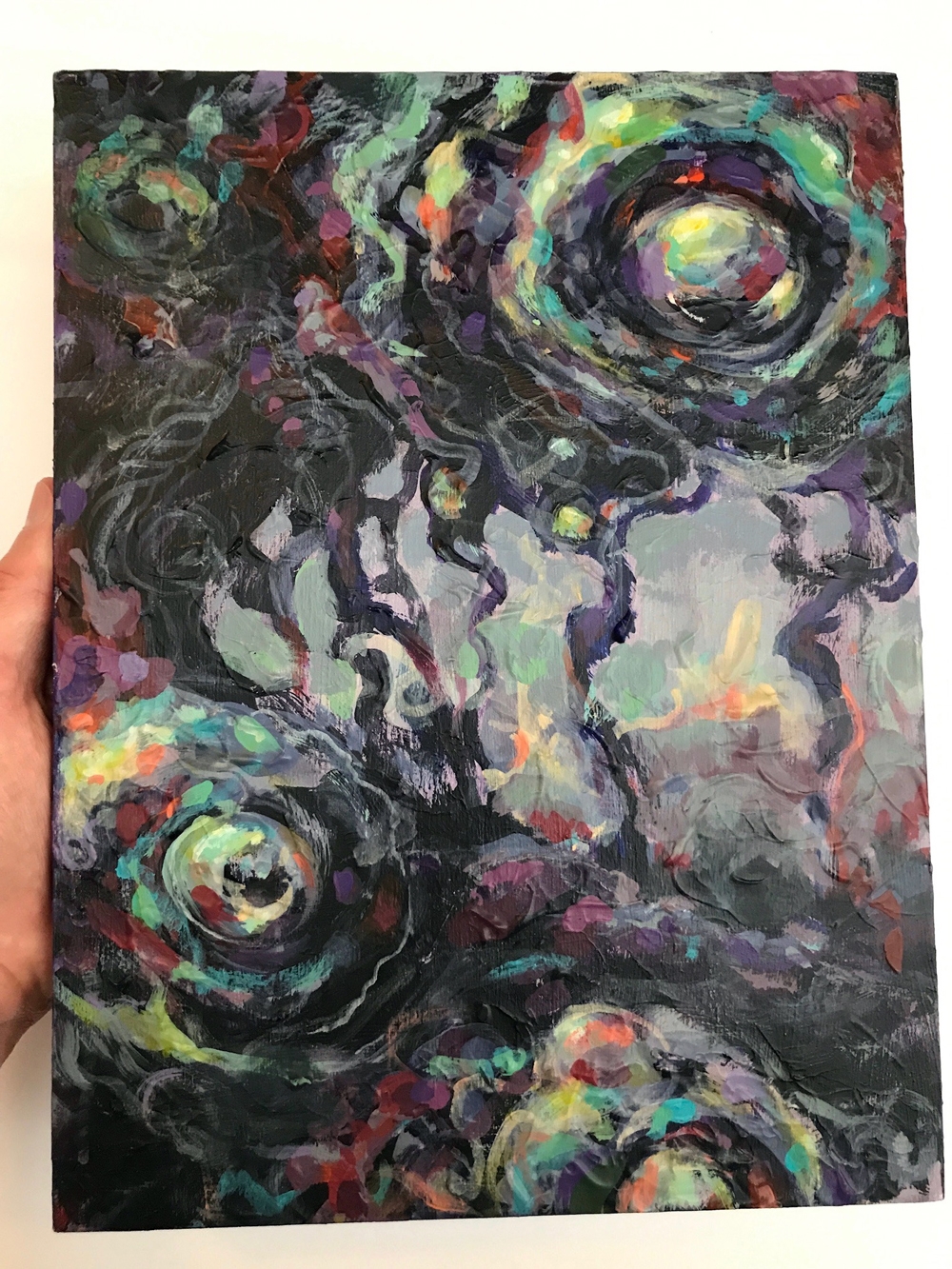

However, the writing had been on the wall for a while. Derek had been looking for ways out. He’d become a lecturer and eventually a professor teaching design at Centennial College on the east side of Toronto. And, his doodling during faculty meetings was frankly getting out of hand. Each session with the other profs would fill notebook pages with long, complex tentacles, random globules, and weird, ghostly eyes. Imagine Mars Attacks meets the Beholder from Dungeons & Dragons, or a mutant squid rising from a deep ocean trench to establish a new civilisation somewhere near Pluto.

His paintings share elements of his creative process with his doodles, tempered and channelled perhaps, by his years spent studying at the Ontario College of Art and Design University. “The same archetypes tend to flow into the image whether it is a painting or a doodle or a drawing or whatever,” says Derek. “One common thing is the process. I try not to go into any of it with a very resolved idea of what the content is going to be and let it evolve along the way. Once something takes shape, then I take measures to resolve it or make a composition out of it in some way.”

Sometimes a little sketching takes place, but there is very little actual planning. Derek spent a lot of time mapping each image out when he was an illustrator, so part of the release of being a painter is to surrender to the process and see where it goes. What’s the art actually about? Well, it’s nothing specific but it seems to be coming from a strange place in Derek’s imagination.

The eyeball connection

“There is definitely a science fiction element in my work,” he says. “I won’t deny that and the eyeball connection cannot be denied. If you look back at my digital work though, when I had creative freedom on a project, this stuff would come through then too. If you look at what I’m doing now as opposed to even a few years ago, you’ll notice that the content in the paintings is vague, less obvious, not quite fully-formed. There are very few eyeballs and recognisable tentacles. When I look back at the work as pieces build up, it is as if I have created some kind of vague realm with its own inhabitants.”

Derek usually works on a group of images at the same time. They can seem to fall together as a series – perhaps because of the colour groups used, or because of visual motifs – but that’s never the intention. He begins by investigating surfaces by size and substrate. Many of his works are on plywood, though lately he’s been drifting back to canvas. He spends a period of time looking at the blank boards, sizing them up mentally and distilling his ideas. Then he grabs his paints and starts working. Acrylics are his main painting medium, but he loves building up three dimensional surfaces within the paintings, using plaster of Paris. There can be a lot of layering and building up, and plywood is good for this because it can take a lot of abuse. Once the painting starts, it’s a matter of deciding when to stop.

He explains: “The paintings just start to become things over time and once they start to reveal something – if I like it and I think it is right for the panel – I will resolve it and work on every aspect of it that I feel needs it. I am trying to stop working earlier because I take photos on my phone at various stages and when I look back I sometimes like them better earlier in the process. This all sounds very calculated but it is only now that I tell you about it that I’m articulating it for the first time. Truth be told, I try to not think too much at all in hopes that I am tapping into something else, maybe subconscious. Does that make me a surrealist? I don’t know. I like to be a bit more gestural in my approach but again, the label doesn’t matter, only the process of creating itself matters.”

My space

All the action goes down in Derek’s basement studio in his home just off Danforth Avenue – Toronto’s Greek district. At one time it was a fully decked out digital studio with big monitors, graphics tablets, Macs, scanners and the kind of ergonomic chair an illustrator needs when they spend 15 hours a day working. Now a lot of that’s been removed and it’s a painting space, large enough for Derek to stand back and observe the images from a distance as he develops them. The work happens in bursts, in between periods of gazing.

Another trapping of the digital illustrator – Derek’s website – has disappeared as well. He has intentionally kept his work in the realm of the physical world for the most part, though he has set up an Instagram account and shares some paintings on Facebook as well. His main audience now is found through exhibitions, and there have been several so far. One has recently finished at The Flying Pony gallery in Toronto. In 2016, he showed at The Corridor Gallery, and earlier this year at The Pilot – both also in Toronto. However, he hasn’t been pushing hard to break the gallery scene. Despite the many differences between the worlds of applied and fine art, it still seems to have too many of the characteristics of the field of work Derek has left behind.

“Galleries aren’t smorgasbords,” he explains. “The work they show is indicative of the style they’re going to cycle through and that is ultimately determined by their market. My work just isn’t pretty wall decoration for rich homes, so I don’t see myself fitting into anything around here. I can see a connection with the lowbrow movement, but in terms of formal qualities I think my work doesn’t synch with the refined surfaces many of those artists work with. I might be too rough around the edges and too painterly for that group too. I don’t think I fit in anywhere.”

He continues: “The second reason is because it kind of makes it a business. If I were to be picked up by a gallery, there would be an obligation to the gallery and they may even want to have input into what I produce. I don’t like the idea of that either, so I am torn and just doing it myself for now.”

The journey continues

Like the paintings themselves – as wild, colourful and imaginative as they are – Derek Lea has set off into the world of painting without a real destination. It’s a form of release, of expression, and he’s seeing where it takes him. He’d like to make more sales, but then again he’s been selling imagery most of his professional life. His place in the world of art is uncertain, and he doesn’t really care.

“I took up painting to be an artist rather than a hired gun. However, many of the artists that inspired me to paint were also illustrators and my work is often criticised for occupying the interstitial space between illustration and painting – in terms of content, mostly. Usually it is meant in a negative way by those who believe that art is the domain of galleries only and that there are rules. But this is who I am and this is what I do.”

He concludes: “So there you go. I am able to ignore the naysayers and just carry on because there is no consequence when nothing is on the line. It is very liberating to create just because you feel like it. You don’t get that as an illustrator.”